Excited to share our latest published study in The European Journal of Development Research. Access here: https://lnkd.in/g9YrYB6E

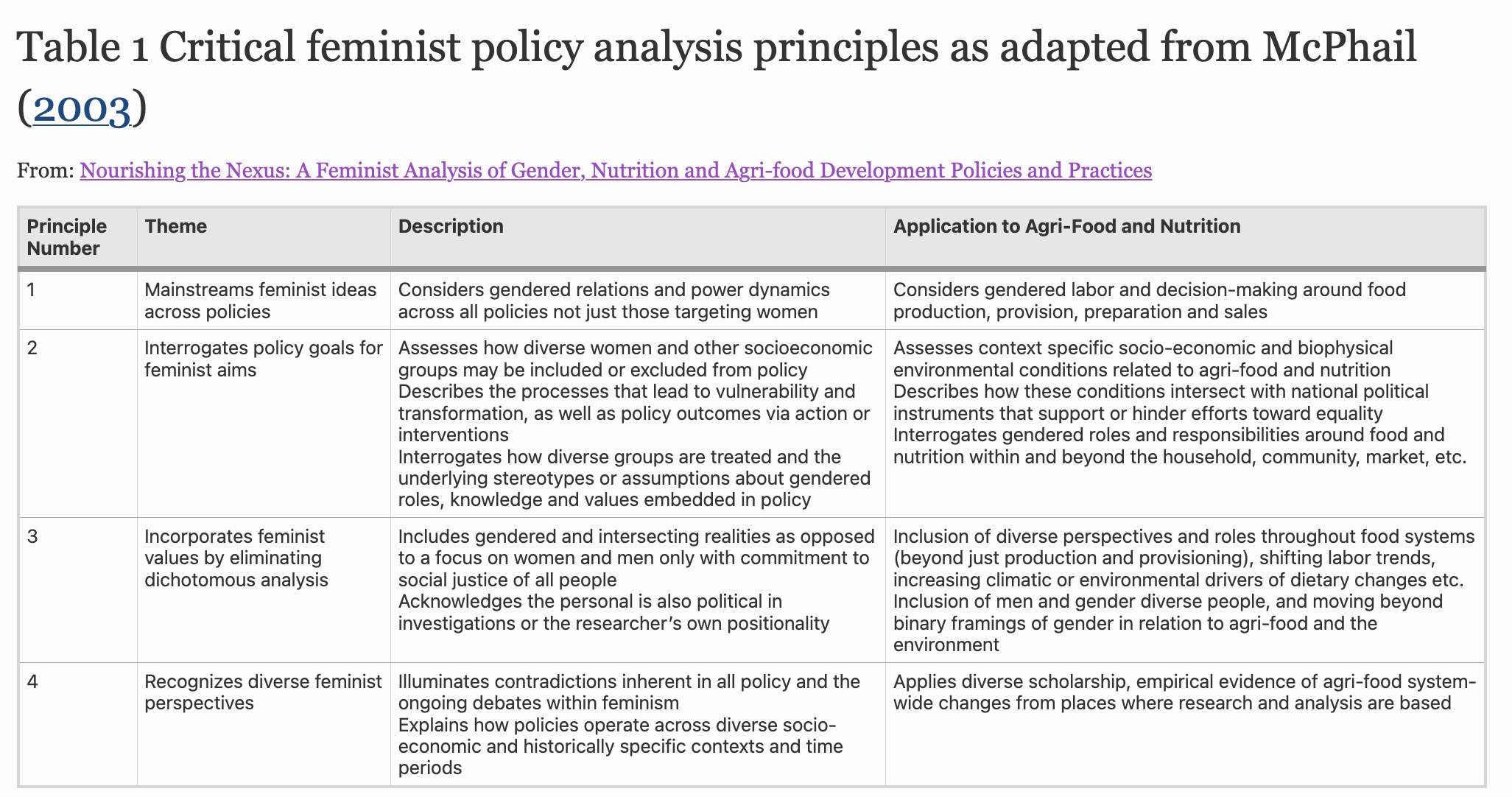

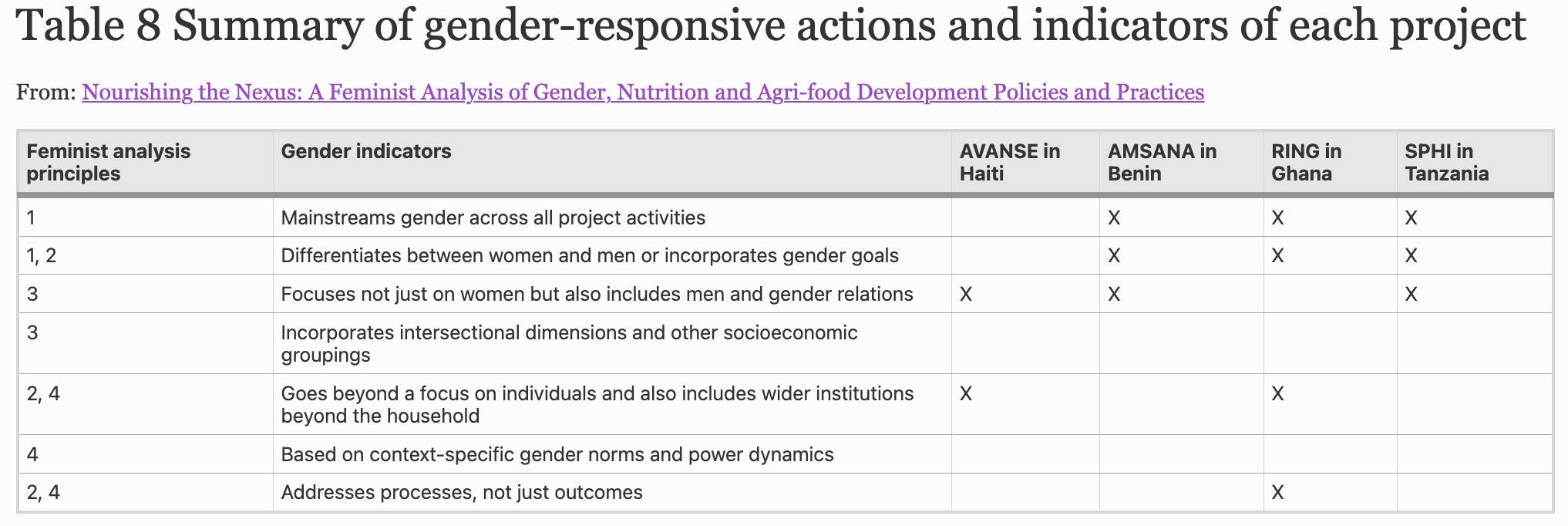

We investigate how agri-food & nutrition policy & practice address gender inequality with examples from Haiti, Benin, Ghana & Tanzania.

We find that the widespread emphasis on gender equality in policy and practice generally ascribes to a gender narrative that includes stereotypes of static, homogenized conceptualizations of food provisioning and marketing.

These narratives tend to translate to interventions that use and objectify women’s labor by funding their income generating activities and care responsibilities for other benefits like household food and nutrition security without addressing underlying causes of their vulnerability, making them worse not better.

We argue that policy and interventions must prioritize locally contextualized social norms and environmental conditions, and consider further the way wider policies and development assistance shape social dynamics to address the structural causes of intersecting inequalities.